Links to external resources

What Do We Know about the Impact of Microfinance?

Microfinance changed their lives

Microfinance, self-employment to curb poverty, says IFC

What MFIs can teach Wall Street

The Financial Power of the Poor

What is microfinance?

The International Bank of Bob: Connecting Our Worlds One $25 Kiva Loan at a Time

Kiva

Background

Traditionally, banks have not provided financial services, such as loans, to clients with little or no cash income. Banks incur substantial costs to manage a client account, regardless of how small the sums of money involved.

For example, although the total gross revenue from delivering one hundred loans worth $1,000 each will not differ greatly from the revenue that results from delivering one loan of $100,000, it takes nearly a hundred times as much work and cost to manage a hundred loans as it does to manage one.

The fixed cost of processing loans of any size is considerable as assessment of potential borrowers, their repayment prospects and security; administration of outstanding loans, collecting from delinquent borrowers, etc., has to be done in all cases.

There is a break-even point in providing loans or deposits below which banks lose money on each transaction they make. Poor people usually fall below that breakeven point. A similar equation resists efforts to deliver other financial services to poor people.

In addition, most poor people have few assets that can be secured by a bank as collateral. As documented extensively by Hernando de Soto and others, even if they happen to own land in the developing world, they may not have effective title to it. This means that the bank will have little recourse against defaulting borrowers.

Seen from a broader perspective, the development of a healthy national financial system has long been viewed as a catalyst for the broader goal of national economic development (see for example Alexander Gerschenkron, Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, Joseph Schumpeter, Anne Krueger ). However, the efforts of national planners and experts to develop financial services for most people have often failed in developing countries, for reasons summarized well by Adams, Graham & Von Pischke in their classic analysis ‘Undermining Rural Development with Cheap Credit’.

Because of these difficulties, when poor people borrow they often rely on relatives or a local moneylender, whose interest rates can be very high. An analysis of 28 studies of informal moneylending rates in 14 countries in Asia, Latin America and Africa concluded that 76% of moneylender rates exceed 10% per month, including 22% that exceeded 100% per month.

Over the past centuries practical visionaries, from the Franciscan monks who founded the community-oriented pawnshops of the 15th century, to the founders of the European credit union movement in the 19th century (such as Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen) and the founders of the microcredit movement in the 1970s (such as Muhammad Yunus) have tested practices and built institutions designed to bring the kinds of opportunities and risk-management tools that financial services can provide to the doorsteps of poor people.

While the success of the Grameen Bank (which now serves over 7 million poor Bangladeshi women) has inspired the world, it has proved difficult to replicate this success. In nations with lower population densities, meeting the operating costs of a retail branch by serving nearby customers has proven considerably more challenging.

Although much progress has been made, the problem has not been solved yet, and the overwhelming majority of people who earn less than $1 a day, especially in the rural areas, continue to have no practical access to formal sector finance.

Microfinance has been growing rapidly with $25 billion currently at work in microfinance loans. It is estimated that the industry needs $250 billion to get capital to all the poor people who need it. The industry has been growing rapidly, and concerns have arisen that the rate of capital flowing into microfinance is a potential risk unless managed well.

Boundaries and principles

Ensuring financial services to poor people is best done by expanding the number of financial institutions available to them, as well as by strengthening the capacity of those institutions. In recent years there has also been increasing emphasis on expanding the diversity of institutions, since different institutions serve different needs.

Some principles that summarize a century and a half of development practice were encapsulated in 2004 by Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) and endorsed by the Group of Eight leaders at the G8 Summit on June 10, 2004:

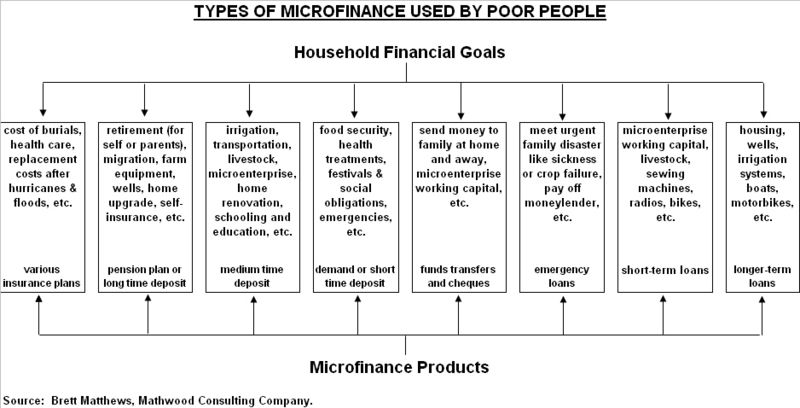

- Poor people need not just loans but also savings, insurance and money transfer services.

- Microfinance must be useful to poor households: helping them raise income, build up assets and/or cushion themselves against external shocks.

- “Microfinance can pay for itself.” Subsidies from donors and government are scarce and uncertain, and so to reach large numbers of poor people, microfinance must pay for itself.

- Microfinance means building permanent local institutions.

- Microfinance also means integrating the financial needs of poor people into a country’s mainstream financial system.

- “The job of government is to enable financial services, not to provide them.”

- “Donor funds should complement private capital, not compete with it.”

- “The key bottleneck is the shortage of strong institutions and managers.” Donors should focus on capacity building.

- Interest rate ceilings hurt poor people by preventing microfinance institutions from covering their costs, which chokes off the supply of credit.

- Microfinance institutions should measure and disclose their performance – both financially and socially.

Microfinance is considered as a tool for socio-economic development, and can be clearly distinguished from charity. Families who are destitute, or so poor they are unlikely to be able to generate the cash flow required to repay a loan, should be recipients of charity. Others are best served by financial institutions.

Financial needs of poor people

In developing economies and particularly in the rural areas, many activities that would be classified in the developed world as financial are not monetized: that is, money is not used to carry them out.

Almost by definition, poor people have very little money. But circumstances often arise in their lives in which they need money or the things money can buy.

In Stuart Rutherford’s recent book The Poor and Their Money, he cites several types of needs:

- Lifecycle Needs: such as weddings, funerals, childbirth, education, homebuilding, widowhood, old age.

- Personal Emergencies: such as sickness, injury, unemployment, theft, harassment or death.

- Disasters: such as fires, floods, cyclones and man-made events like war or bulldozing of dwellings.

- Investment Opportunities: expanding a business, buying land or equipment, improving housing, securing a job (which often requires paying a large bribe), etc.

Poor people find creative and often collaborative ways to meet these needs, primarily through creating and exchanging different forms of non-cash value.

Common substitutes for cash vary from country to country but typically include livestock, grains, jewelry and precious metals.

As Marguerite Robinson describes in The Microfinance Revolution, the 1980s demonstrated that “microfinance could provide large-scale outreach profitably,” and in the 1990s, “microfinance began to develop as an industry” (2001, p. 54).

In the 2000s, the microfinance industry’s objective is to satisfy the unmet demand on a much larger scale, and to play a role in reducing poverty.

While much progress has been made in developing a viable, commercial microfinance sector in the last few decades, several issues remain that need to be addressed before the industry will be able to satisfy massive worldwide demand.

- The obstacles or challenges to building a sound commercial microfinance industry include:

- Inappropriate donor subsidies

- Poor regulation and supervision of deposit-taking MFIs

- Few MFIs that meet the needs for savings, remittances or insurance

- Limited management capacity in MFIs

- Institutional inefficiencies

- Need for more dissemination and adoption of rural, agricultural microfinance methodologies

Community Development

Community development is a broad term applied to the practices and academic disciplines of civic leaders, activists, involved citizens and professionals to improve various aspects of local communities.

Community development seeks to empower individuals and groups of people by providing these groups with the skills they need to affect change in their own communities. These skills are often concentrated around building political power through the formation of large social groups working for a common agenda. Community developers must understand both how to work with individuals and how to affect communities’ positions within the context of larger social institutions.